Incredible new inventions are introduced to the world every year. Typically, technology gets the most attention and the most funding. But, not all inventors develop technology like the smartwatch. Products that save water in the shower, keep a paint brush from drying out between coats on a wall, and that make doing dishes easier can be just as lucrative as a consumer electronics device, but getting funding for a venture in home and garden can be much more challenging than landing venture capital for a new app.

September 29th was National Inventor’s Day. In honor of all the inventions that have been created over the years that we as consumers take for granted, I have created the following advice. My tips and tricks are based on lessons I learned by launching my own products into the marketplace over the years, including the Gumleaf Gutter Guard. Combined with the additional experience I have gained as a licensing company for other people’s inventions like the Handy Camel bag clip and the Garden Thorn.

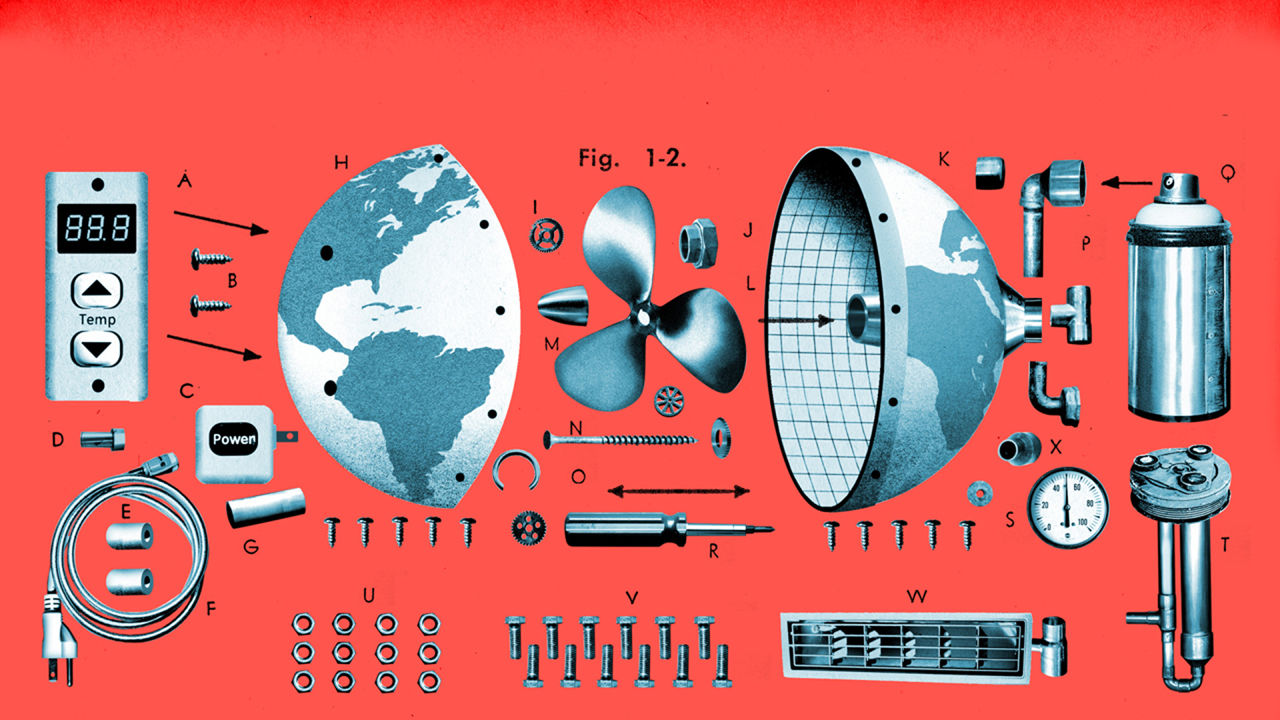

Do not engage a professional to build your prototype until you have built several your self. Many prototypes don’t work how you originally planned for. When you are ready to license your invention or start crowdfunding it, you will need a professional working prototype. Until then, you need to know your idea will indeed perform as intended. Find friends or mentors within the community that have access to 3D printers and CNC machines. Often having an inventor “buddy” makes things much more enjoyable. Schools and colleges are also investing more in the latest equipment and the students are becoming extremely knowledgeable about these products, there is a great resource right there.

When you start putting your invention on paper, make sure that you can explain your product and be able to demonstrate it easily if it gets to market. The biggest struggle is educating the end consumer on what your product is and how it works. Often at tradeshows you get a great response from those kind enough to stop and watch your life changing innovation. However, when sitting on a retail shelf you will not have the liberty to demonstrate to each speed walker heading to the next aisle on a mission. Your packaging and product needs to be eye-catching and simple enough to explain the need for the product in 15 seconds or less.

Before beginning any prototyping, market research, or planning what to spend your millions on after you hit it big, start by scouring the internet for similar products and patents. Talk to a patent attorney and avoid writing your own patent. It can cost a company interested in licensing a product idea upwards of $250,000 to bring that idea to market. A licensing company is not going to invest that type of capital in a product that has a weak patent or simply patent pending status because the product is unprotected at that stage. The sooner you can apply for a professionally written patent, the better.

Even if your idea is original and there are not patent issues to be concerned with, there are some ideas that I still recommend letting remain as ideas. If a market is already crowded with products, it might be better to invest your time and money into a more unique concept. Research is vital at every step of the startup process, but is incredibly important at the onset. Inventors need to spend time studying their intended industry to learn about similar products, potential customer base, pricing levels the market supports and future opportunities. Failure to investigate a market can result in an inventor wasting time to create a product for which there will be no investors, licensors or buyers.

Finally, I always advise people to identify and learn from mistakes. One of the first lessons people experience in life as children is to learn from mistakes. If a square block does not fit in the round hole, move to the next hole. Inventors who are rejected by an investor or retailer need to rally in the moment. Leaving a meeting, ending a call or email exchange without asking what went wrong or why the answer was “no” is a critical error. Not asking why they are being rejected can keep inventors spending money when major problems are present. And then, the cycle of rejection will simply continue until the idea collapses or funding runs dry.