I went into the meeting with every intention of saying yes. But the answer to my own seemingly simple question changed all that, and I knew in an instant that my life would never be the same. What I could not have imagined was how quickly Mother Merrill would metamorphose into something I would not even recognize.

It was October 2001, just a few weeks after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. Merrill Lynch had been forced out of its offices in the neighboring World Financial Center. The new president and eventual CEO, E. Stanley O’Neal, was temporarily using our office at 717 Fifth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. A few days before, as part of his broad reorganization, O’Neal had removed me from my twin positions as chairman of Merrill Lynch International and president of the International Private Client Group. He had asked me to stay on as Vice Chairman of Merrill Lynch & Co. to focus on our most important client relationships throughout the world. I was initially skeptical. I had become increasingly concerned about O’Neal’s vision for Merrill Lynch, about how he was starting to shape his administration, and about his shabby treatment of some of my fellow executives. However, conversations with several ML colleagues whose judgement I respected convinced me to give the new role a try. We scheduled another meeting.

Stan was never big on small talk, so just as I was settling into my chair he said: “I hope that you’re here to accept the job. I want you to be a core part of my team. We are going to have to change a lot of things about the way this place is being run. As soon as we get rid of Komansky, we can get started running this place the right way.” Wow! I started at him in disbelief. Here was the new president talking about discarding his nominal superior, David H. Komansky, the chairman and chief executive officer. O’Neal rambled on until I asked him where he stood on the Principles.

“The Principles” were our mantra at Merrill Lynch. Charlie Merrill and my father had built the firm on a core set of values, and through the years they had been carried forward by their successors. Every chairman and CEO up to O’Neal had always felt and acted as though they stood on the shoulders of the leaders who had preceded them. Dan Tully, Komansky’s predecessor, capsulized these Principles and now they were displayed prominently in every Merrill Lynch office throughout the world. In our design offices, they were written in the local language. And they were etched in the concrete of our headquarters in New York:

CLIENT FOCUS.

RESPECT FOR THE INDIVIDUAL.

TEAMWORK.

RESPONSIBLE CITIZENSHIP.

INTEGRITY.

Tully revered them and always referenced the Principles whenever we had to make difficult decisions. “Okay,” he would ask in a weekly Executive Committee meeting, “is this really in the client’s best interests?” But when I asked O’Neal about them, his face distorted with anger and I could see the arteries throbbing in his neck.

O’Neal launched into a scathing attack against “Mother Merrill”—he said the words the way a sick man names his disease—and he ridiculed the Principles and the culture that had made the company revered by both its customers and employees. As he ranted on, I grew angrier and felt my cheeks quivering and the veins throbbing in my own neck. Clearly this man cared nothing about our heritage or our prestige in the business world. Finally, I interrupted him. I had heard enough. “Stan,” I said, “thank you for your offer but I can’t work for you.” I stood up and walked out, to the silent amazement of O’Neal.

Back home in Connecticut that night, doubts began to fester as I tried to fall asleep. Had I acted impulsively rather than rationally? Was it the wrong decision—a huge mistake? Abruptly leaving a firm where my father had worked for forty-five years, finishing at the very top, and a place where I had been for twenty-eight years was not an easy decision. I knew that I would be disappointing many colleagues as well as my family. And I understood that I would be giving up many millions in future compensation.

But the next morning I awoke refreshed, with a sense of relief. I knew I had made the right decision. I looked out the window at a glorious autumn day. Every leaf looked like a flower. I got into my car and began driving north—first on Interstate 95, then on Interstate 91. As I passed the exit for Holyoke, Massachusetts, I thought about my father, who had been born and raised only a few miles from there in South Hadley Falls. Also nearby was Amherst College, where both Charlie Merrill and my father had studied and from which I graduated in 1971.

At that moment I was sure that my father would have been proud of my decision because it was based on principle—his Principles. The Merrill Lynch culture that I loved and respected was going to change dramatically, and I could not be a party to it. I could not be a member of this new management team.

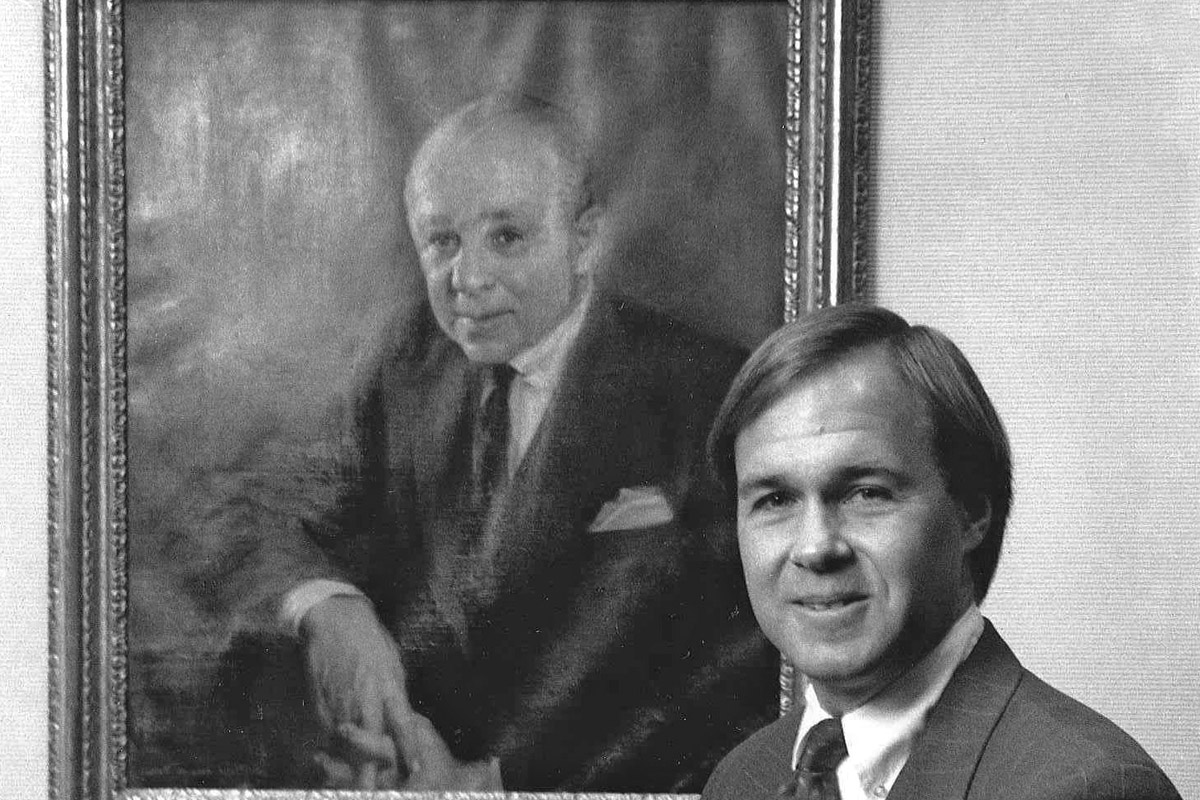

While I was driving, I suddenly thought of the matryoshka, the Russian nesting dolls, in Dave Komansky’s office. Dave had been presented with these as a gift when he succeeded Dan Tully as CEO in 1997. There were ten dolls, each with the face of a Merrill Lynch leader, beginning with Charlie Merrill. Next came my father. Then Mike McCarthy, George Leness, Jim Thompson, Don Regan, Roger Birk, Bill Schreyer, Dan Tully, and Dave Komansky. The dolls got progressively larger from Merrill up. The symbolism of the dolls was that each era of Merrill Lynch grew from what was inherited from the prior one and that each new leader built on the success of his predecessor rather than relied on what he could achieve alone. Each of us stood on the shoulders of those who came before us, those who built our successful firm and created a powerful and enduring culture. It was our responsibility to maintain the essence of what came before us while moving into the future. It was our obligation to adopt change without throwing out the Principles that were our solid foundation. It was our obligation to preserve the culture.

By the time I crossed the border into Vermont that day, I could really see that autumn had taken a firm grip on the landscape. The change is dramatic because Vermont has outlawed billboards and all you see is the vista. I drove past trees in gorgeous Van Gogh colors, past farmland that had been harvested to stubble. My destination was Sugarbush, a ski resort that I and a few other investors had purchased on September 10, the day before the terrorist attack.

One nagging thought refused to go away, however, and it clung to my brain like a barnacle on a bull. Stanley O’Neal was dead wrong when he characterized my company—my former company—as inefficient, paternalistic, and bloated. On the contrary, Merrill had become one of the leading investment banking and private wealth firms in the world. We had a global footprint that was unmatched and envied by our competition.

We were proud to wear “the Bull” on our sleeves and in our hearts, and we felt privileged to be a member of Mother Merrill’s family. The “bloated” firm that O’Neal was about to disassemble had earned a record $3.8 billion the prior year, had a pre-tax margin of 21.3 percent, and had a return-on-equity of 24.2 percent. For the forty-eight consecutive quarter we had led the Global Underwriting league tables with 13.3 percent market share, and we ranked No. 3 in global mergers and acquisitions, with very little difference between us and No. 1. Our global research was No. 1 in the world, and we were the dominant secondary equity trading firm in the world. Our private wealth business held $1.5 trillion in client assets and our global asset management business managed $557 billion. We had 72,000 employees, 21,200 financial advisors, and 975 offices forty-four countries around the world. In the first quarter of 2001, our stock price hit a record high of $80.

However, O’Neal had no interest in continuing the culture that had allowed our firm to prosper. In my opinion he was enabled by a Board of Directors who valued their positions and compensation as directors more than they valued a culture that required integrity and respect. They allowed short-term profitability to blind their views of the highly-leveraged and risky business Merrill would become, and they allowed a small group of greedy individuals to destroy an icon.

The real story of Merrill Lynch had to be written. There was a reason why Arthur Levitt, the former chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission under President Clinton, called Merrill Lynch “the only firm on Wall Street with a soul.” This is a mostly positive story about a firm that grew into greatness through principled leadership and a core set of values that shaped its culture and brought Wall Street to Main Street after World War II. Through innovation and principled leadership, it became one of the world’s leading and most venerated financial firms. For the hundreds of thousands of us who knew the real Mother Merrill, our experience there was like catching lightning in a bottle. Unfortunately, the years after 2001 were not the same.

This has been an excerpt from Catching Lightning in a Bottle: How Merrill Lynch Revolutionized the Financial World by Winthrop H. Smith, Jr.

This article is brought to you by Winthrop H. Smith, Jr. as part of Alister & Paine Magazine’s Direct Publishing. Mr. Smith is a former EVP of Merrill Lynch & Co., member of the Executive Management Committee, and Chairman of Merrill Lynch International. He is one of few people who has known every CEO at Merrill Lynch and shares the intimate details of his first-hand experiences in his book, Catching Lightning in a Bottle: How Merrill Lynch Revolutionized the Financial World.